Using First Principles Thinking to Solve Our Hiring Heroes Problem in the United States

Photo by Unsplash

The challenge of reintegrating a nation-state’s military veteran back into its civilian workforce has persisted since the time of Caesar Augustus in Rome circa 13 BC. Therefore, it is time to innovate on this millennia-old communications problem and solve it, at least in the US, and

First Principles Thinking is a time-tested problem-solving technique. The first step in applying the power of first principles thinking is to break the veteran hiring problem down into its seven fundamental elements, what Aristotle called

first principles, to accurately define it. Then we can use five applicable philosophical razors to separate, i.e.,

shave off, our extant assumptions from the identified first principles to clear our clouded current thinking. Doing so then allows us to reassemble the first principles in a new way, creating an innovative solution to veteran hiring through first principles thinking, which we can implement, at least in the United States, using nine proven tools and techniques.

Keywords: Veterans, veteran hiring, veteran reintegration, United States

Millennia-Old Problem of Military Veteran Reintegration, i.e., Hiring

Nation-state programs to reintegrate their professional soldiers and sailors back into the civilian work force is a challenge that has persisted since Caesar Augustus in Rome circa 13 BC. While many factors contribute to this complex problem, a primary component of the challenge is that the technical experience of the profession of arms, when spoken about in military terms and concepts, correlates easily or directly into very few civilian occupations, if any. As such, generation after generation of military veterans continue to struggle to find and keep meaningful post-military service employment commensurate with their experience because they cannot communicate their valuable experience in terms and concepts that civilian hiring managers understand.

Problem Reduction

The challenge of veteran hiring has many components, which we will explore here. First, the process to transform a civilian into a warrior—Soldier, Sailor, Airman, or Marine—at least in the United States and many related NATO countries, is immersive, strenuous, lasts for a couple of months to several years, and is based on a clear, cogent, exhaustive instruction manual delivered by senior, experienced professionals at arms. The Service Member’s service exit event, however, is only one to three days in length, covers multiple topics, devotes only one day to civilian job identification, preparation, hunting, networking, and technology usage, and may or may not be delivered by veterans, which means a shared sense of empathy, sympathy, and culture may be missing from the instruction. Additionally, in this short class, veterans, i.e., “vets”, are encouraged to Stop speaking military, write a targeted resume, create a LinkedIn profile, network, and find a mentor, all without any practical how-to tips provided. The assumption is that the vets have the same level of understanding and intuition about what these tools are and how to use them as the instructor.

Compounding these veteran components, two hiring manager-centric components enter the equation. The first is that it is highly statistically probable that the civilian hiring manager may not be or may not even know a vet, as only about five percent of the United States’ three hundred and eighty million citizens have ever served in a military uniform (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). In fact, this veteran author has, on multiple occasions, had civilians thank him for his noble work with animals, misunderstanding his veteran status or vet title to be associated with another type of “vet”, a veterinarian. Additionally, exacerbating this lack of familiarity is Hollywood’s perpetuation of inaccurate myths and stereotypes about military members and veterans, which makes the vet population even more alien to them. Some of the most popular myths and stereotypes string together like this: all vets qualified on a weapon, that all of them carried, and that all of them used to shoot individuals or groups with, which gave them post-traumatic stress disorder, and they did so under orders, yelled at them constantly, so they must only know how to follow orders, because most of them are likely under-educated as well. These threads weave into a conclusionary narrative that vets cannot fit into a civilian workplace based on collaboration, high emotional intelligence, strong individuality, in a modern office setting, full of individuals and teams solving problems in sometimes stressful situations.

All these assumptions and challenges stem from a communications problem. Veterans do not do an effective job of communicating how their past experience translates into future capability, which is what the civilian hiring manager is listening for. And the civilian hiring managers do not understand how this unfamiliar military experience fits into their civilian work environment, which means they do not accurately value it. Therefore, the value of the veteran’s experience gets lost in the translation between the military and civilian work forces.

Millennia-Old Method of Reasoning; First Principles Thinking

The complexity of this veteran hiring problem is the result of these fundamental challenges coupled with millennia of assumptions made in the face of continually evolving work force needs, technological advances, laws, hiring practices, and continued labor specialization. It therefore warrants the diligent and deliberate application of first principles thinking. First principles thinking has been used to solve complex problems by many great minds for centuries (Clear, n.d.). It first requires the identification of this problem’s essential components, those base elements that Aristotle called “first principles” because they “are the first basis by which a thing is known”, so that we can then separate our first principles from the layers of assumptions (Aristotle, n.d.). Adding philosophical razors to our analysis can help us achieve this separation of first principles from assumptions, so that we can then reassemble them into a new solution; innovating on veteran hiring using the power of first principles thinking. To this end, the next section identifies and discusses the eight first principles of veteran hiring, and its following companion section identifies the five philosophical razors that we can use to ‘shave off’ these assumptions and complexity to ensure we are truly examining the problem’s first principles (Otto, 2022).

On First Principles

First principles are the fundamental elements of an issue or argument. We can find examples of them in physics, philosophy, language, geometry, and engineering. In physics, think about the relationship exposed when we decompose a molecule down to an atom, which is decomposed down to a nucleus, then a proton, to arrive at the molecule’s first element, the building blocks known as quarks and gluons. The US Department of Energy’s Office of Science defines “Quarks and gluons are the building blocks of protons and neutrons, which in turn are the building blocks of atomic nuclei” (U.S. Department of Energy, n.d.). Likewise, the philosophical first principle statements

All humans age and

You and I are humans, allow us to deduce, i.e., reason, that

We age. Additionally, think of the first principles of language, which in the case of the English language are the twenty-six letters of its alphabet. These twenty-six letters can be arranged into thousands of words, which can be arranged into thousands of sentences, then paragraphs, then chapters, and finally books. Finally, to illustrate reasoning up from first principles, i.e., “first principles thinking”, think of a tank, a bicycle, a pair of skis, and a motorboat (Clear, n.d.). If we assembled them in a new innovative way, what vehicle would we create? Right. A snowmobile! This first principles thinking has been used to solve complex problems throughout the ages by great minds such as Aristotle, Euclid, Edison, Tesla, Boyd, and Musk (Pearson, 2017).

On Razors

In philosophy, like psychology, we have mental shortcuts we can use as simple tools to help us distill simplicity from complexity in our thinking (Duggan, 2018). And while psychology would call these mental shortcuts heuristics, in philosophy we call them razors (The Decision Lab, n.d.). While dozens of razors exist, five of them are useful in helping us shave off assumptions in veteran hiring from our previously discussed first principles. In short, they are Occam’s, Hume’s, Hitchens’, and Duck’s razors, to which we will add Sagan’s Standard because it significantly enhances Hume’s razor in our analysis.

Occam’s razor states that if we are presented with two or more arguments that include all necessary data to describe the argument, position, or phenomenon, we should choose the simplest one as the proper explanation. Extending this notion of sufficient data or evidence to support an argument or position, we have Hume’s and Hitchens’ razors coupled with Sagan’s Standard. Hume asserted that causes must be sufficiently able to produce the effect assigned to them, meaning that the almost imperceptible wind created by a butterfly flapping its wings is not sufficient to explain a house-damaging forty-knot gust of wind (Elledge, 2023). Famous astronomer Carl Sagan extended Hume’s razor by stating his standard that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” (Life Lessons, 2019). Additionally, Hitchens used his razor to assert that claims made without evidence can be dismissed without evidence, and Hanlon argued to “Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by incompetence or stupidity” (Elledge, 2023). And finally, the razor that binds the rest is the Duck test. Simply put, if the thing under consideration looks like a duck, walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck. These five razors are essential in identifying the eight first principles of veteran hiring.

Innovative Modern Solution: Applying the Power of First Principles Thinking to Solve Military Veteran Hiring

Identifying the seven first principles of veteran hiring and separating them from the many assumptions surrounding this issue allows us to reassemble them into a new innovative solution to solve this persistent societal problem. These first principles are presented next, as is the solution we can innovate from them. Following that discussion, we then discuss the hardest part of any change, implementation.

Eight First Principles of Veteran Hiring

From this author’s own experience transitioning out of military service, conversing with tens of thousands of military members in transition and vets already transitioned over the past eight years, and successfully placing over twelve thousand of them into meaningful, lucrative post-service careers to enjoy post-military prosperity, the author has identified eight principles of veteran hiring.

The first and second first principles of veteran hiring are that management has four functions, which are planning, organizing, leading, and controlling, and that management has several subsets, examples of which are Information Technology Management, Quality Management, Human Resources Management, Financial and Accounting Management, Sales and Marketing Management, and Production Management. The third first principle of veteran hiring is that vets have germane yet latent experience applicable in any civilian organization, because they have broad, deep experience solving complex, time-bound, resource-constrained problems; within large bureaucratic organizations rife with rules, regulations, customs, courtesies, norms, and SOPs; through a multitude of individuals, teams, bosses, peers, and subordinates. This problem-solving experience also means that they have the intangible skills of curiosity, responsibility, critical thinking, accountability, and commitment.

The fourth and fifth first principles of veteran hiring are that vets have two types of experience, general and specialized, and that vets have a high aptitude to learn highly specialized things fast. For example, most vets have general management experience running teams, shops, and ships’ departments, while doing technical things like operating and maintaining planes, tanks, and submarines. Moreover, they are given their occupations based on what occupations they test into, i.e., what they are capable of doing, as they enter their service (Military.com, 2012). They are then sent to a schoolhouse upon their entrance experience previously discussed, learn a very technical job quickly, and then are immediately sent to the field, flight line, or fleet to perform that occupation. These responsibilities often entail stakes as high as loss of limb or life on the line; theirs or others. This also contributes to a high aptitude for adapting to change fast, as they go from schoolhouse to command, to schoolhouse to command, and so on over their entire career. This means their capacity for productivity and their ability to produce continually go up, which increases their overall capability.

The sixth principle is that all vets share at least a few common experiences, which forms a solid foundation of trust, capability, and productivity. Examples vets can draw from are stressful, physical inductions and orientations at schoolhouses, standing watches, qualifying on firearms, forming up into units which move from point A to point B in sharp unison, and getting “chow”, i.e., food. And when vets do not do these things exactly right, as one unit, they do a lot of physical exercise, a favorite modality being the ubiquitous push up. They also experience many medical shots, haircuts, inspections, and sleep deprivation.

They are bonded under duress, which blurs boundaries, and which brings us to our seventh and eighth first principles of veteran hiring, that vets make better helpers of vets and that vets do not like talking about themselves. While well intentioned, a non-vet helping a vet does not have full and complete empathy and sympathy, a shared intimate cultural bond is missing, and because vets are team and we oriented, not me oriented, talking about oneself and one’s accomplishments is discouraged. We always recognize that one of our teammates was better, faster, stronger, more capable, that the team is stronger than the individual, that there is always a higher headquarters, and that heroes we are not. Our heroes are the ones of us that did not come home with us.

Now that we have identified our problem as a communications problem, and identified and separated our eight first principles of veteran hiring from our assumptions using five razors, we are ready to innovate a new modern solution to an age-old problem and implement it through seven specific actions.

Applying the Power of First Principles Thinking to Veteran Hiring

Our innovative solution consists of first educating vets and civilian private and public employers, i.e. Corporate America, on the first principles of veteran hiring, then teaching vets “provable fluency” (Wright, 2020), and then teaching Corporate America

military speak, which informs both parties in the communication exchange, allowing them to communicate more clearly what is needed by Corporate America, so it can be presented by the vet. Therefore, the communication problem is solved but needs specific solutions to be implemented, which is the next and final topic.

Conclusion

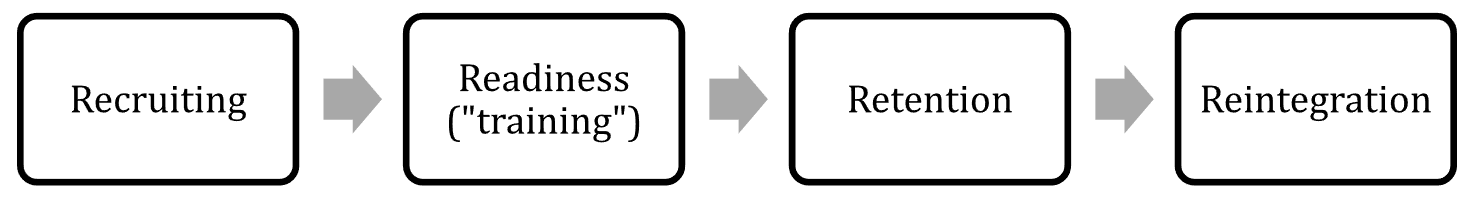

At least in the context of the US and NATO organizations that recruit, train, i.e. “ready”, retain, and reintegrate vets back into their work forces, Corporate America can learn the vets’ language of

military leadership with five easy, cost-effective actions (see Figure 1 below). Candidates are recruited, then they are trained and deployed based on their aptitude, testing, and occupation training, then they’re developed over their tenures, and finally they’re reintegrated back into the civilian workforce, the focus of this paper. The following suggestions provide military service exit training to enhance reintegration.

Figure 1. US Model of Veteran Creation (original figure)

First, their HR department personnel and managers can use the Department of Labor’s online tool O*Net to cross walk civilian and military occupations at the skills and competencies level to discern capability to perform now based on what the vet did in the past (Onet Center, n.d.). Second, the Society of Human Resources Managers (“SHRM”) offers online training and certification demonstrating an employer’s capabilities to attract, hire, and retain veterans (Veterans at Work, n.d.). Third and fourth, civilian hiring managers can hire translated, trained, and certified vets or have their current vet hires translated, trained, and certified by the author’s firm (Vets2PM, n.d.), and create understanding in your managers to understand vet resumes with the author’s book How To Speak Civilian Fluently! because it contains a “Cognate Crosswalk” (Wright, 2020), which are words similar in two languages, to help them translate on the fly during interview preparation. Fifth, companies can hire a prior-service vet-turned recruiter into their HR department to review and translate resumes. While implementation does take work, these activities open the candidate aperture by another eighteen million veterans according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (U.S. Department of Labor, 2023).

And vets can learn the language of Corporate America, which is management. First, corporations should have someone create a short “onboarding orientation video” outlining the company, its mission, industry, and customers, with support resources identified so the Vet knows where to go for which types of help when. Second, like your managers, provide your vets with a copy of How To Speak Civilian Fluently! because it extends the orientation and on-boarding experience at a low cost, because the vet reader gets a feel for what accounting, marketing and finance do, and what P&L, JIT, and OJT mean, and how org charts are used. Your civilian organization becomes more familiar to them, which makes them more autonomous and resilient, and more likely to stay. Third, ensure that your vet hires come with the Department of Labor Work Opportunity Tax credit, so you get the $9,6000.00 tax credit per vet hire for which you are eligible. Do not be one of the companies leaving their portion of the annual unclaimed $64 billion tax credits (Washburn, 2020).

And finally, fourth, SHRM suggests using situational or behavioral interview techniques that use open-ended questions to tease out their capabilities because veterans do not like talking about themselves, as it is counter to the organizational and team-based we culture. A situational interview “gives the interviewee a hypothetical scenario and focuses on a candidate's past experiences, behaviors, knowledge, skills and abilities by asking the candidate to provide specific examples of how the candidate would respond given the situation described”, and behavioral interviews “focus on a candidate's past experiences, behaviors, knowledge, skills and abilities by asking the candidate to provide specific examples of when he or she has demonstrated certain behaviors or skills as a means of predicting future behavior and performance” (SHRM, n.d.). For example, if you ask them what they did, they may say I ran a dining facility, or I ran an armory, or I was a machine gunner. However, these are examples of managers managing inventories, budgets, and PP&E for their organizations, while taking care of the people’s well-being, health, care, and professional development.

The popular STAR method is used in a behavioral interview to “objectively measure a potential employee’s past behaviors as a predictor of future result” (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, n.d.). The popular STAR model may prove helpful to many hiring managers. They ask the candidate to tell them about a situation, task, action, and result produced in a past task or project. It demonstrates the vet’s capability and skills within the context of what problem occurred, what tasks the team performed, which of those actions were taken by the vet, and the results produced. Closed ended questions with no solicitation of situation to provide context will not uncover the value of the breadth and depth of experience the vet brings.

References

- Aristotle. (n.d.). The Metaphysics.

- Clear, J. (n.d.). First Principles: Elon Musk on the Power of Thinking for Yourself. James Clear. https://jamesclear.com/first-principles

- Duggan, J. (2018). 5 Philosophical Razors to Help You Win Any Argument. Medium. https://medium.com/@jossduggan/5-sharp-philosophical-razors-to-help-you-win-any-argument-4c4b6177fcc0

- Elledge, J. (2023). Some Philosophical Razors. The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything. https://jonn.substack.com/p/some-philosophical-razors

- Life Lessons. (2019). 9 Philosophical Razors You Need to Know. Critical Thinking. https://lifelessons.co/critical-thinking/philosophical-razors/

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (n.d.). Using the STAR Method for Your Next Behavioral Interview (Worksheet Included). Career Advising & Professional Development. https://capd.mit.edu/resources/the-star-method-for-behavioral-interviews/

- Military.com. (2012). Your Military Job Can Depend On Your ASVAB Test Score. Military.Com. https://www.military.com/join-armed-forces/asvab/asvab-scores-and-military-jobs.html

- Onet Center. (n.d.). O*Net Resource Center. Onetcenter.Org. https://www.onetcenter.org/

- Otto. (2022). Diversion: 5 Philosophical Razors For Critical Thinking That Will Shave Your Mind. Sharpologist. https://sharpologist.com/5-philosophical-razors-for-critical-thinking/

- Pearson, T. (2017). The Truth about How Creativity Really Works. Medium. https://medium.com/the-mission/the-truth-about-how-creativity-really-works-46623efb6775

- SHRM. (n.d.). Job Interview Questions. Shrm.Org. https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/tools-and-samples/interview-questions/pages/default.aspx

- The Decision Lab. (n.d.). Hanlon’s Razor. The Decision Lab. https://thedecisionlab.com/reference-guide/philosophy/hanlons-razor

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2023). Economic News Release: Employment Situation of Veterans Summary. Economic Releases. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/vet.nr0.htm

- U.S. Department of Energy. (n.d.). DOE Explains...Quarks and Gluons. Office of Science. https://www.energy.gov/science/doe-explainsquarks-and-gluons

- U.S. Department of Labor. (2023). Employment Situation of Veterans — 2022. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/vet.pdf

- Veterans at Work. (n.d.). SHRM Foundation Certificate Program. Veteransatwork.Org. https://www.veteransatwork.org/certificate/

- Vets2PM. (n.d.). Lifetime Access to Proven Certification Training Corporate Talent Services. Vets2PM Post Military Prosperity. https://vets2pm.com/

- Washburn, C. (2020). An Estimated $64.8 Billion in Work Opportunity Tax Credits (WOTC) Go Unclaimed by Employers Each Year. Veteran Tax Credits. https://www.veterantaxcredits.com/white-paper/

- Wright, E. A. (2020).

How To Speak Civilian Fluently! Independently Published.

Apply first principles thinking yourself?

Would you like to apply first principles thinking yourself and have your problem-solving experience published in the First Principles Thinking Review? Then be sure to check out the submission guidelines and send us your rough idea or topic proposal. Our editorial team would be happy to work with you to turn that idea into an article.

Share this page

Disclaimer : The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in submissions published by FIPS reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views held by FIPS, the FIPS team or the authors' employer.

Copyrights : You are more than welcome to share this article. If you want to use this material, for example when writing an article of your own, keep in mind that we use cc license BY-NC-SA. Learn more about the cc license here .

What's new?