First Principles Thinking as a Tool for Researchers to Overcome the Challenge of Conceptualization

At the foundation of every scientific study must lie a clear definition of what is being studied. Such a definition of key concepts is reached through the process of conceptualization, to which there exist two main approaches: the classical (or first principles thinking) approach and the prototype (or analogical thinking) approach. Through the example of finding an adequate definition for the concept of ‘democracy’, both approaches to conceptualization are demonstrated in practice. This article compares the effectiveness of both approaches before proposing a model for the more rigorous and reliable first principles thinking approach.

The Challenge of Conceptualization

When one thinks of the names commonly associated with the first principles thinking method—not least the likes of Socrates or Aristotle—it is easy to believe that first principles thinking is a tool with which only the greatest of people can do the grandest of things. While it may be true that some of the most innovative minds in history have used first principles thinking to produce a number of groundbreaking and revolutionary ideas, one should not be intimidated by their precedent. In fact, if you are a researcher or have ever conducted a research project, then there exists a strong likelihood that you are also a first principles thinker. The only question is whether or not you are aware of it.

In any field of research, one of the initial tasks of the researcher is to clearly define the subject matter of his or her study, a process known as conceptualization. Dimiter Toshkov (2016) defines concepts as “the building blocks of scientific reasoning, and of human cognitions in general,” adding that they “are essential for core scientific activities such as theory formation, description, categorization, and causal inference” (p. 84). That being said, if a social science researcher were to conduct a study on democratic government, he or she would first have to begin by defining what exactly is meant by the concept of ‘democracy’. There are two main approaches to tackling this problematic challenge: first principles thinking or thinking by analogy.

The Classical Approach to Conceptualization

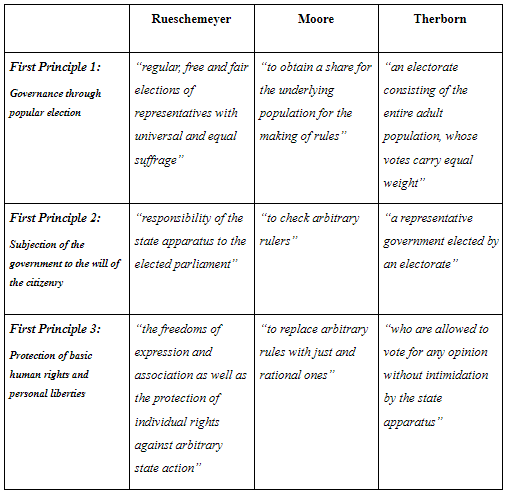

According to the so-called classical approach to conceptualization, “concepts have rule-based definitional structure,” meaning that they are “defined by a set of individually necessary and jointly sufficient conditions that delimit unambiguously what qualifies as [their] empirical realizations” (Toshkov 2016, 86). Simply stated, a concept’s definition is not effective unless it clearly outlines exactly what that concept is and what it is not. Following Aristotle’s explanation of a first principle as “the first basis from which a thing is known”, the researcher must begin by deconstructing the concept of democracy into its underlying first principles in order to be able to adequately define it (Irwin 1988, 3). What qualities must a state possess in order to be considered a democracy? In the view of German sociologist Dietrich Rueschemeyer and colleagues (1992), being a democracy entails:

[...] first, regular, free and fair elections of representatives with universal and equal suffrage; second, responsibility of the state apparatus to the elected parliament… ; and third, the freedoms of expression and association as well as the protection of individual rights against arbitrary state action. (p. 43)

Therefore, according to the conceptualization of Rueschemeyer et al., the underlying first principles of democracy are (1) governance through popular election, (2) subjection of the government to the will of the citizenry, and (3) protection of basic human rights and personal liberties. American sociologist Barrington Moore (1966) defines the development of democracy as:

[...] a long and certainly incomplete struggle to do three closely related things: to check arbitrary rulers, to replace arbitrary rules with just and rational ones, and to obtain a share for the underlying population for the making of rules. (p. 414)

Similarly to that of Rueschemeyer et al., Moore’s conceptualization of democracy rests on a set of three first principles. Specifically, those are (1) subjection of government to the will of the citizenry, (2) protection of basic human rights and personal liberties, and (3) governance through popular election. Finally, for the Swedish sociologist Göran Therborn (1977), a democracy is a regime that:

[...] has a representative government elected by an electorate consisting of the entire adult population, whose votes carry equal weight, and who are allowed to vote for any opinion without intimidation by the state apparatus. (p. 4)

A pattern is now becoming increasingly evident. Like Rueschemeyer et al. and Moore, Therborn deconstructs the concept of democracy into the first principles of (1) having a government that is subject to the will of the citizenry, (2) governance through popular election, and (3) protection of basic human rights and personal liberties. Based on this common set of first principles uncovered by deconstructing the three scholars’ respective views of democracy, the researcher can now begin to reconstruct a conceptualization of democracy that is concrete and precise. Figure 1 provides a comparison of each scholar’s first principles for the concept of democracy.

The question that remains is whether the resulting set of first principles can be considered appropriate and comprehensive. After all, the classical Greek conceptualization of democracy can be etymologically deconstructed into a single first principle: dēmos + kratia, which translates to ‘rule by the people’. In the 21st century, however, a conceptualization so broad as to permit slavery in a democratic state—as was the case in ancient Greece—would be considered too minimalistic by modern standards, putting into question whether just three first principles would be similarly insufficient. On the other hand, the researcher must likewise be careful not to let positive questioning be overtaken by normative considerations. While the researcher may view the state’s recognition of homosexual marriage as something that should be common in democracies, it would be very dangerous indeed to consider this a first principle of democratic government itself, as it would result in an extremely narrow set of cases of exemplary democracies around the world throughout human history.

The Prototype Approach to Conceptualization

In contrast to the classical approach, concepts under the prototype approach “are not defined by clear rules based on necessary and sufficient conditions but have a ‘family resemblance’ structure,” meaning that “an object is considered to belong to a concept if it sufficiently resembles a prototype member of this concept” (Toshkov 2016, 87). Returning to the challenge of conceptualizing democracy, the prototype approach would not require the researcher to deconstruct the concept in search of underlying first principles, but instead to find an ideal example of what a democracy should be to serve as a point of reference for analogical thinking. Unlike first principles thinking, which aims to solve challenges by first deconstructing them to their core elements, analogical thinking duplicates solutions applied to similar contexts. What country comes to mind when one says ‘democracy’?

When searching for an ideal example of a democracy to serve as a point of reference, one is likely to think of Sweden sooner than of El Salvador. The reason for this is that Sweden exemplifies many characteristics that are commonly associated with democratic government, such as economic development and political stability, whereas the high poverty and violent crime rates of El Salvador are commonly associated with undemocratic government. However, if economic development and political stability are to be considered characteristics essential to the concept of democracy then Saudi Arabia should qualify along with Sweden, when in fact it is an absolute monarchy while El Salvador is a presidential republic. With El Salvador unable to meet the democratic standards set by Sweden, thinking by analogy leaves the researcher not with a solid definition of democracy but with a merely superficial idea of what one should look like.

A Model for Conceptualization with First Principles

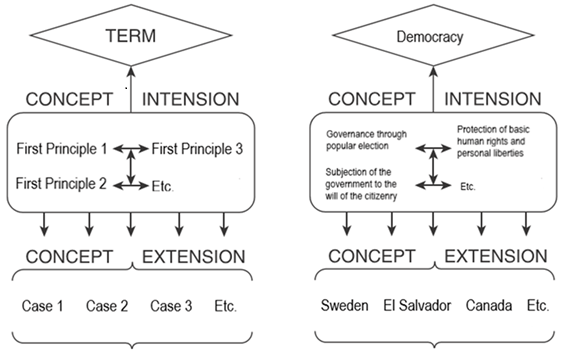

Figure 2 proposes a model for the process of conceptualization according to the classical approach, or by first principles thinking. The term refers to the word that represents the concept to be defined. In this case, the term ‘democracy’ is the label used to represent the abstract form of government that is the subject of the study. The initial step in the process is concept intension, or deconstructing the term to uncover the underlying first principles. Based on the views of the three sociologists that have been examined, possible first principles of democratic government are governance through popular election, subjection of the government to the will of the citizenry, and protection of basic human rights and personal liberties. Secondly, concept extension refers to finding cases that embody those first principles in the empirical world. Such cases of democracy would be Sweden and El Salvador, amongst others.

Naturally, one could argue that the inability of the Salvadoran government to protect its citizens from gang violence might undermine the first principle of protecting basic human rights and personal liberties. In a similar manner, chronic corruption and cronyism could be argued to undermine the first principles of governing through popular election or subjecting the government to the will of the citizenry. If such doubts arise, the process of conceptualization must be applied again in order to clearly define what exactly is meant by concepts like ‘human rights’, ‘personal liberties’, and ‘popular election’. Which rights are all humans entitled to? What liberties are inalienable to every individual in society? Who can and cannot vote in a popular election? Asking such questions is the key to deepening one’s own understanding of the initial concept of democracy and constructing a more solid conceptual framework on which to base one’s study.What is certain is that there always remain more first principles to be found. And it is by pursuing these first principles—by incorporating first principles thinking into his or her methodology—that the researcher can finally overcome the challenge of conceptualization.

References

- Irwin, T. (1988). Aristotle’s First Principles. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Moore, B. (1966). The Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Rueschemeyer, D., Huber Stephens, E., & Stephens, J. D. (1992). Capitalist Development and Democracy. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Therborn, G. (1977). The Rule of Capital and the Rise of Democracy. New Left Review, 1(103), 3–41.

- Toshkov, D. (2016). Research Design in Political Science (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Apply first principles thinking yourself?

Would you like to apply first principles thinking yourself and have your problem-solving experience published in the First Principles Thinking Review? Then be sure to check out the submission guidelines and send us your rough idea or topic proposal. Our editorial team would be happy to work with you to turn that idea into an article.

Share this page

Disclaimer : The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in submissions published by FIPS reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views held by FIPS, the FIPS team or the authors' employer.

Copyrights : You are more than welcome to share this article. If you want to use this material, for example when writing an article of your own, keep in mind that we use cc license BY-NC-SA. Learn more about the cc license here .

What's new?